Mountain Tai does not give away a grain of soil, and therefore it can become large. The rivers and oceans do not refuse the tiniest trickle, and therefore they can become deep.By encompassing everything from high literature to the popular one, a man can examine into all that concerns heaven and humankind, while being inclusive and embracing the diversity of different schools of thought, he is not far from putting forth his views as a school of interpretation. In this spirit, the Chamber of Rongjian (‘Inclusion and Embrace’) houses all sorts of collectanea (congshu), where first rate scholarship in the studies of Chinese classics, history, Buddhism and philosophy can also be found here. By engaging with these important works constantly, the learner is expected to advance in the studies of Sinology and enjoy the splendour of the pantheon of academia.

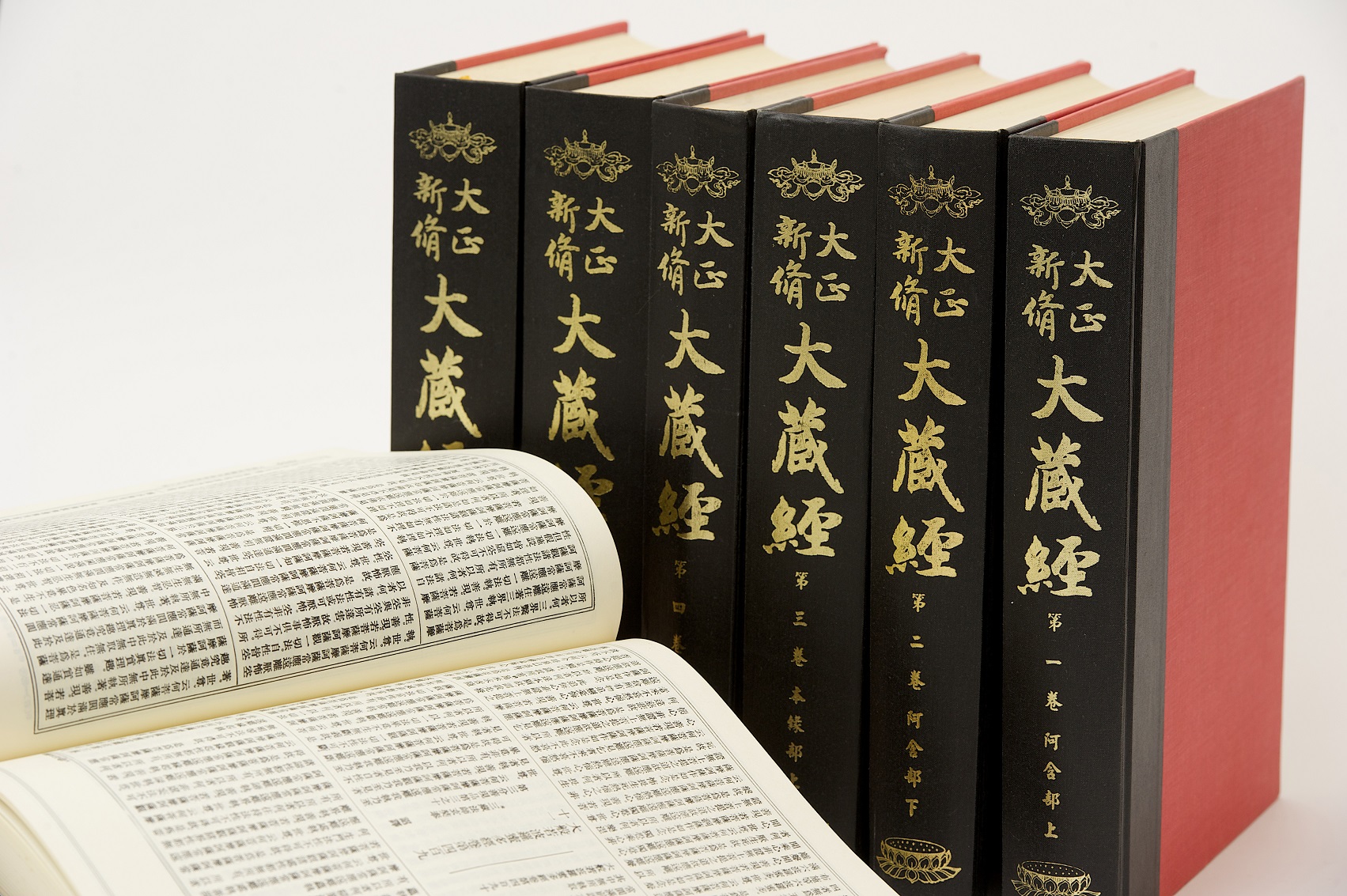

Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō

After the spread of Buddhism to the East, Buddhist canonical scriptures had been translated (from Sanskrit and other Indic and Central Asian languages), written (in Classical Chinese), collected and collated by generations of believers, leading to a substantial increase in the number of scriptures. In order to put the increasingly disorganized canon in order, they were collected, compiled and collated into Tripiṭaka, or the Buddhist Canon. Rather than a one-time project, it is through the efforts of generations of scholar monks and converted intellectuals that the process of canonization was gradually completed. According to historical records, the compilation of Tripiṭaka occurred more than a dozen times in China, eight times in Japan and three times in Korea during the Koryŏ period. Since the texts collected in these Tripiṭaka were all written in Chinese script, they are also under the subcategory of Chinese Tripiṭaka, so as to differentiate from other canons such as the Tangut Tripiṭaka or Japanese Tripiṭaka.

The earliest attempt of systematically compiling a Chinese Tripiṭaka can be traced back to the Kaibao period (968-75) under the reign ofEmperor Taizu of the Song Dynasty, and the resulted Kaibao Tripiṭaka has served as the basis for later compilers. The most famous Chinese Tripiṭaka among all is probably the Qianlong Tripiṭaka or popularly known as Longzang (‘Dragon Tripiṭaka’) commissioned by Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty; however, the more accessible edition is the one edited by Japanese scholars (chief editors ) and first published in the thirteenth year of Taishō (1924), under the title of Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō. Owing to the discovery of Dunhuang manuscripts, the Tripiṭaka Sinica (aka Zhonghua dazangjing) published in Mainland China since 1984 added a considerable amount of content from the manuscripts.

The copies of Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō (1924-34; edited by Takakusu Junjirō, Watanabe Kaigyoku, etc.) in the JAS collection were donated by Professor Ku Cheng-mei and her spouse, Professor Chong Kim-chong, and is kept in the Rongjian Chamber. Besides being a wealth of Buddhist canon translated into Chinese,this version also preserved some original sacred texts of Brahmanism and a large quantity of early Buddhist woodblock prints. Therefore, the Tripiṭaka is not only indispensable to the studies of Buddhism, philology and history, but also has tremendous value in art history.