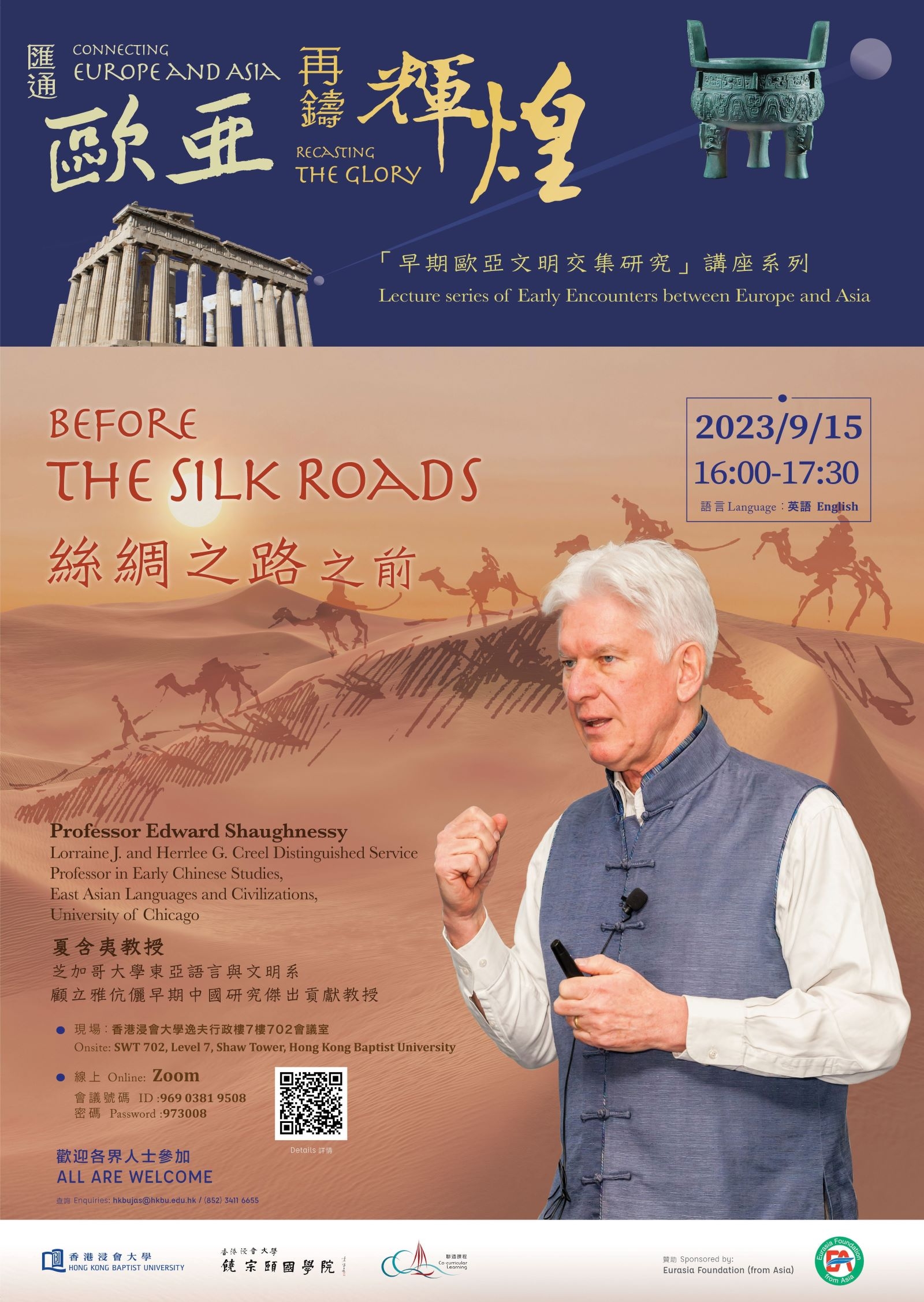

Connecting Europe and Asia, Recasting the Glory: Lecture series of Early Encounters between Europe and Asia

Lecture 1: Before the Silk Roads

2023/9/15 │ 16:00–17:30

Professor Edward Shaughnessy

Lorraine J. and Herrlee G. Creel Distinguished Service Professor in Early Chinese Studies, East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Chicago

- Abstract: Long before Zhang Qian 張騫 (d. 114 BCE) made his celebrated trip through Central Asia, people were passing back and forth along the entire breadth of Eurasia. Chinese silk has been found woven into the air of a female mummy from Egypt dating to about 1000 BCE. On the other hand, there is evidence of the knowledge of—if not necessarily—the physical presence of Egyptian-style papyrus in China about the same time. Other examples of contact across Eurasia include horse-drawn chariots from no later than 1200 BCE down to the pyramids covering tombs in the mid-Warring States period and even the statues of soldiers near the tomb of Qin Shihuang (d. 210 BCE). In this talk, I will present comparisons of these types of artifacts on either end of what would become the Silk Roads.

- Language: English

- Summary (Recorded by Guan Jinglin)

Taking archaeological material as its wellspring, Professor Edward Shaughnessy in his lecture titled ‘Before the Silk Road’ introduced the situation pertaining to cultural exchange between the civilisations of Europe and Asia prior to the Qin dynasty.

First, Professor Shaughnessy shared his comparative research into several genres of European and Asian artifacts. In his paper ‘Three Studies of East-West Cultural Exchange c.1000 BCE’, he draws attention to three types of artifact: Chinese silk found on the body of an female Egyptian mummy; ancient Egyptian papyrus excavated in an early Western Zhou dynasty tomb at Gaojiapu; and carved statuary of heads of people of Caucasian race in the early Western Zhou dynasty. The first two of these indicate that as early as c.1000 BCE, there was already contact at some level between China and ancient Egypt, and the third proves that the Zhou people already had a relatively deep recognition of people of Caucasian race. Professor Shaughnessy has also published a research paper ‘The Origins and Historical Significance of the Chinese Chariot’ that, through comparison of chariots unearthed at Anyang in China and excavated specimens and cliff paintings in Central Asia, finds that their workmanship comes from the same mould, with Central Asian chariots appearing at least three hundred years earlier than their Chinese counterparts, which therefore serves as proof that chariots first entered China from North-west Asia in c.1200 BCE. It is more than thirty years since Professor Shaughnessy published this paper, and since then, archaeological circles in China have widely accepted his proposal that chariot technology was imported from territories to the west.

Following on from this, Professor Shaughnessy went on to introduce the research of other distinguished scholars into early cultural exchange between Europe and China, for example, Victor H. Mair and J. P. Mallory’s investigation of a mummy from the Tarim basin in Xinjiang, and their exploration of the true state of prehistoric peoples of the region. Richard Barnhart has compared the royal tomb in Zhongshan with the ancient Greek tomb of King Mausolus and considers that they were similar in structure, and that the architectural style of the latter was perhaps transmitted into China via a Central Asian route and influenced the building of the former. Luka Nickel has compared the terracotta figures of Qin Shihuang’s tomb with ancient Greek sculptures, including the movements of the charioteers, the heads of foot soldiers, and the postures of the people that are modelled, and in all cases found that they resemble one another to some degree, and that from this, the influence of Western sculpture on China can be observed.

From the material supplied by these East-West artifacts, dated c.1000 BCE, it can be proven that before the establishment of the Han dynasty Silk Road, shuttling back and forth across the entire Eurasian landmass was already extremely frequent and purposeful, and thus cultural exchange and linkage between Chinese and Western civilisations could be said to possess a distant wellspring and a lengthy flow downstream.

- Lecture video

HKBUTube

Bilibili

This lecture series is sponsored by Eurasia Foundation (from Asia).