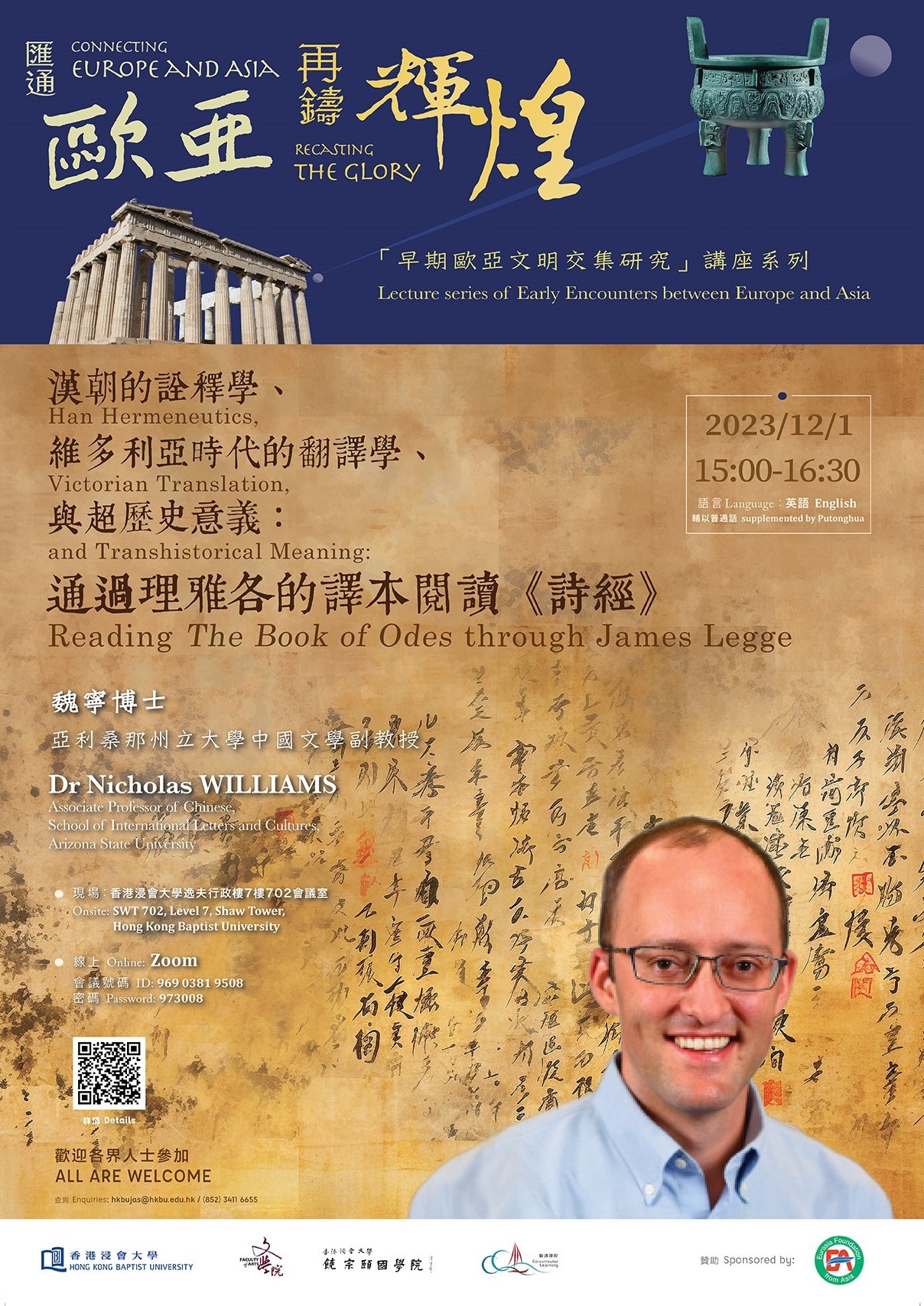

Connecting Europe and Asia, Recasting the Glory: Lecture series of Early Encounters between Europe and Asia

Lecture 10: Han Hermeneutics, Victorian Translation, and Transhistorical Meaning: Reading The Book of Odes through James Legge

2023/12/1│15:00–16:30

Dr Nicholas WILLIAMS

Associate Professor of Chinese,

School of International Letters and Cultures,

Arizona State University

- Abstract:Since the early 20th century, a critique of traditional exegeses of the Shijing 詩經 (Book of odes) has become prevalent among scholars both in China and outside it. The critique takes various forms, but tends to hold that the Mao Commentary of the Han Dynasty politicizes and allegorizes poems that originally had a more straightforward meaning. As a corollary to this view, James Legge’s Victorian translation of the Book of Odes is seen as similarly flawed, since it hews too closely to the traditional interpretations, most of which are derived from the Mao Commentary.

The modern critique is surely correct with regard to several of the poems, in particular a few of the “Airs of the States” whose main subject seems to be romance and not political commentary. But then, this critique was already put forth convincingly during the Song Dynasty and is not entirely new. When applied wholesale to the Book of Odes in its entirety, however, the critique is grossly misguided. Fortunately, the tendency in some recent Chinese-language scholarship has been to rehabilitate—or at least to be much more cautious before overturning—the traditional interpretations. The Mao Commentary, as interpreted and transformed by later Chinese philologists, remains an indispensable resource for understanding the poems.

Thus the corollary dismissal of James Legge’s translation likewise needs to be reevaluated. In historical hindsight, the bold interpretations of Waley do not always rely on any solid evidence having to do with early China at all. Yet Legge’s sometimes awkward, often prejudiced translations and commentary nonetheless attempt a complex negotiation among the Mao Commentary, Zhu Xi, and Qing philology, not to mention the language of Victorian Protestantism. Legge does not aim to or achieve scientific objectivity, but rather, inspired by the accidental alignment between his own rigid convictions and certain Confucian principles, seeks to participate in a transcultural dialogue with his scholarly predecessors in China. The result is a many-layered work that still has much to teach us about how the meaning of the Book of Odes has evolved since the Han Dynasty.

- Language: English (supplemented by Putonghua)

- Summary (Recorded by Guan Jinglin)

In this lecture, Dr Nicholas Williams took perspectives drawn from Han dynasty hermeneutics and Victorian translation as material to make a fresh appraisal of James Legge’s translation of The Book of Odes and through this revealed its transhistorical meaning.

First, Dr Williams cast a retrospective glance at opinions expressed in the Western scholarly world regarding The Book of Odes and surveyed some of the most important translations, for example, Arthur Waley advocated that the original poems of The Book of Odes were characterised by simplicity and directness, and thus during translation into English, reduction of Confucian political tampering with their text should be implemented to the utmost. In the nineteenth century, James Legge’s viewpoint was the opposite of this. His translation of The Book of Odes, published in 1871, sought to elicit correct interpretations from a welter of exegetes ranging from the Han dynasty to the nineteenth century and their commentaries and sub-commentaries, including those of Mao Heng (or Mao Chang) of the Han dynasty, Zhu Xi of the Song dynasty, and Legge’s friend Wang Tao.

After this, Dr Williams took the poem ‘Ye you man cao’ (‘On the moor is the creeping grass’ [Legge’s translation of the title]) from the ‘Zhengfeng’ (Odes of Zheng) section of The Book of Odes, and from the dual perspectives of line-by-line translation and explanatory material, he analysed Waley and Legge’s different methods of translation into English. Waley considered that this poem was an innocent poem of courtship redolent of bucolic shepherd’s songs and rejected the notion that another interpretation was permissible. Legge, on the other hand, records different hermeneutics pertaining to traditional exegesis of this poem as preserved in, for example, the ‘Shi xiaoxu’ (Lesser prefaces to The Book of Odes) and Hanshi waizhuan (The alternative exegesis of the Han redaction of The Book of Odes) and does not come to a single reading of the text. In addition, Dr Williams took the poem ‘Luxiao’ (‘How long grows the southernwood’ [Legge]) from the ‘Xiaoya’ (‘Minor odes of the kingdom’ [Legge]) section, and using lexical items from the text, namely, ‘linglu’ 零露 (falling dew) and ‘xie’ 寫 (speaks in catharsis), he compared them with identical or equivalent items in ‘Ye you man cao’, namely, ‘linglu’ 零露 (falling dew) and ‘xiehou’ 邂逅 (meet by accident). Through this, he considered that Legge’s methods of citing traditional exegesis have established linkage between the two poems and are a much more powerful explanation of them. Compared with more recent sinologists and their emphasis on the primitive folk character of The Book of Odes, Legge’s practice of quoting traditional commentaries and sub-commentaries has taken The Book of Odes and given it a reading that situates it within the field of vision of a wider literary tradition.

Following this, Dr William analysed the origins and principles of Legge’s methods of translation via the background of the times he lived in. The emphasis placed on moral conduct and personal cultivation in the Victorian age has a strong parallel with the Confucian orientation towards moral practice. This meant that when Legge was in the process of translating, although he consistently abided by the original text, he tended more towards absorbing the fruits of early research into it, for example, ‘Shi xiaoxu’. In this context, when Dr Williams analysed ‘Er zi cheng zhou’ (‘The two youths got into their boats’ [Legge]) from the ‘Beifeng’ (Odes of Bei), he drew attention to the phenomenon of how Legge had noticed that early commentaries and sub-commentaries had taken The Book of Odes and connected it to historical events.

In addition, Dr Williams considered that Legge did not uncritically abide by early commentaries and sub-commentaries on The Book of Odes and often borrowed from Zhu Xi’s writings so that he could criticise the Maoshi (The Mao redaction of The Book of Odes). In this context, Dr Williams discussed the concealed metaphor ‘zhoudao’ 周道 (main road) in ‘Feifeng’ (‘Not for the [violence of the] wind [Legge]) from ‘Guifeng’ (Odes of Gui) and the supposed satirical meanings in ‘Sangzhong’ (Legge interprets this as a placename) of ‘Yongfeng’ (Odes of Yong).

In conclusion, the most important four hermeneutical principles adopted by Legge in his English translation are as follows: 1. Individual poems should not be read with their stanzas broken and the meaning extracted out of context. When the context is unclear, subjective assumptions should not be employed to eliminate multiple and varied divergent views. 2. Specific editions should be read in tandem with correlative editions and a broader literary tradition. 3. Creative hermeneutics of early exegesis of the original text should be treated conscientiously. 4. Under ordinary circumstances, early evidence, including excavated documents, is superior to more recent evidence.

- Lecture video

HKBUTube

Bilibili

This lecture series is sponsored by Eurasia Foundation (from Asia).